This article appeared on Caught by the River on 12th September 2020.

At the fulcrum of summer, just before the unsettled weather and the slow decline into autumn, I am visiting Covehithe with my partner Kevin and a friend, Debbie, who I haven’t seen for 35 years. We are in search of fossils and interesting sights.

Covehithe is a few farms, houses and a church near an exposed stretch of North Sea coast. Taking a path through scrub and long grass, we come to the beach. It is an unspoilt place; there is no café, no toilets, not even a fence along the cliffs. Looking south you can just make out Southwold pier and lighthouse. A giant cruise ship and a sailing barge sit on the horizon. On a breezy day like this, the beach has only a few visitors — dog walkers and families huddled behind wind breaks or braving the sea for a swim. The place speaks of impermanence, change, the past — the cliff crumbles like dry, sugary ginger cake. Trees, roots and peat blocks have tumbled from above and lie strewn across the sands, some embedded, others scoured and bleached by sun and waves. The sea is hungry here. The whole Suffolk coast is eroding more than 2.5m a year and is one of the fastest disappearing coastlines in the British Isles.

Today the sea is milky jade, its mood moderately calm. The tide is out, the sky, promising. A few gulls twist the air overhead as we head south, stopping now and then to examine the cliffs and fallen debris. This stretch of coastline is supposed to be good for fossils such as bivalves and shark’s teeth. You could possibly even find a flint axe head. I am new to fossil hunting and pleased with any beachcombing find. The cliff has layers, deposits of white shells with sand and pebbles in between, all laid down 1 to 2 million years ago.

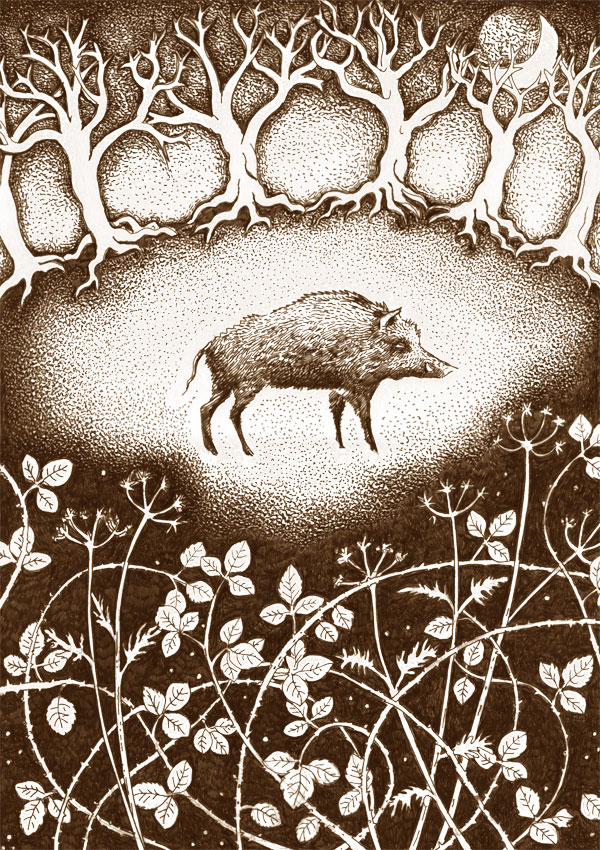

I first became interested in Covehithe through reading Time Song: In Search of Doggerland by Julia Blackburn. I wanted to come and see it for myself, but I didn’t hold out much hope of finding a fossil. I like to imagine myself back 8,000 years, to the end of the last ice age, just before the water spilled down from the retreating ice sheet to flood what we now call Doggerland and form the North Sea. Across the grey waves, beyond the cruise ship and the sailing barge, was land stretching as far as the eye could see. Marshes and mudflats, tundra and rivers, and no English Channel. In my mind I see lagoons, reedbeds, waders, mammoths and walruses. I see nomadic people travelling in small groups, people of shore, wetland and water.

A coast of flux and loss; the subtly shifting edge of one’s imagination — land into sea, sea into land.

The cliff top has a scruffy tuft of woodland. The trees look dark and grave, as if they know their fate. The coast here is also sinking very slowly as part of a rebalancing act with Scotland, which has shed its ice age burden and is in the process of rising. Sand, shell, rock, fossil, tree, root, peat — it is all shifting, succumbing, tumbling, exposing, transforming.

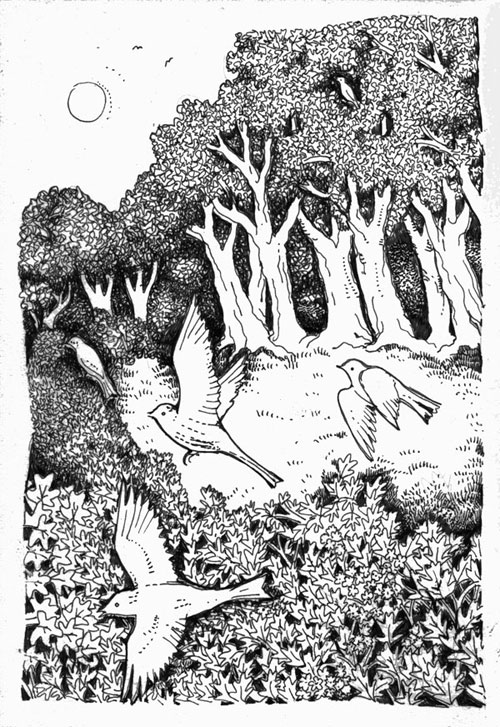

Sand martins peep out from little holes in the orange cliffs. Now and then a bird swoops out and chatters overhead with its neighbours, white-bellied and brown-backed. I approach the cliff to look closer. Hesitant white faces look back.

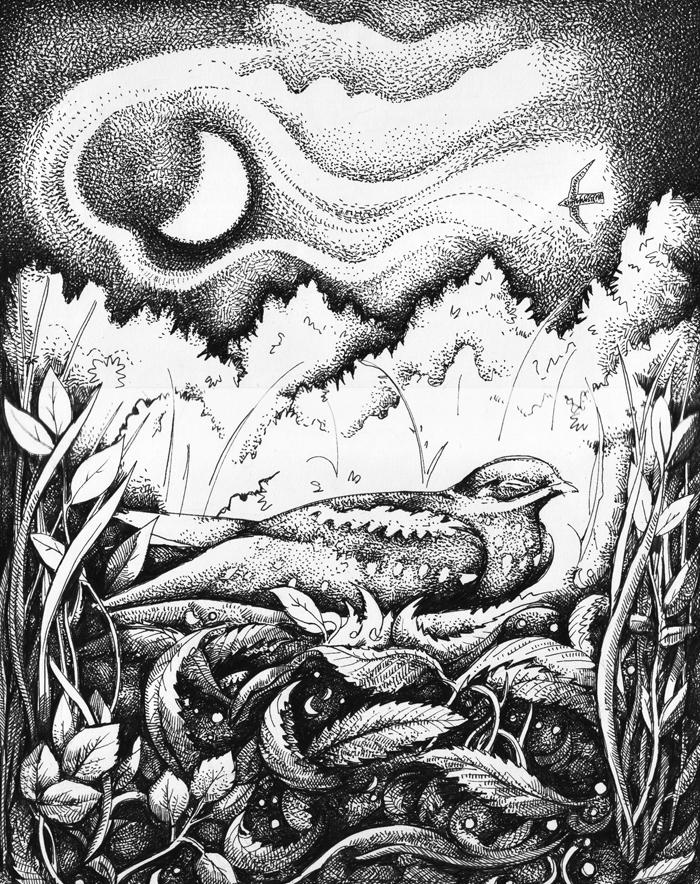

I become fascinated by the dishevelled tree remains on the shore. There is something undignified about these trees. Once robust and sturdy, they now lie bleached and skeletal in up-turned tangles as though caught mid-action in the last throes of life; a shape-shifting assemblage of contorted creatures. One tree reaches a green, algal arm out over the waves.

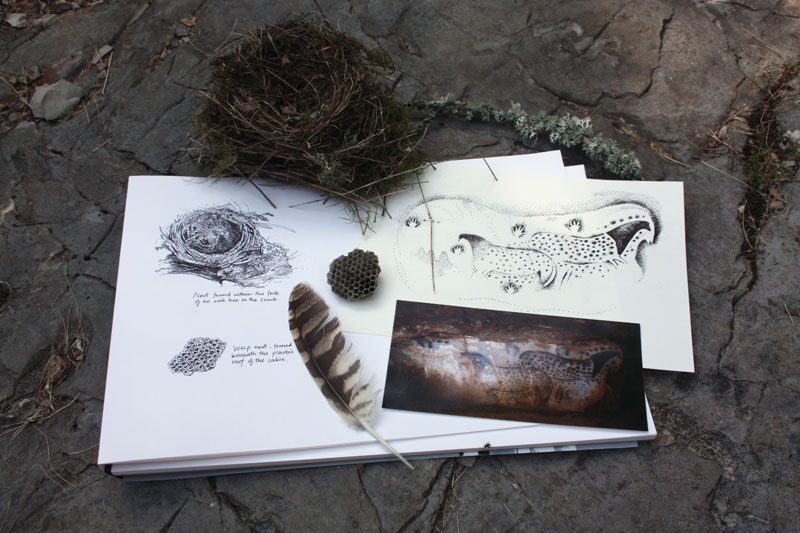

On the beach below Easton Wood, Debbie finds a large, white clam shell fallen from the crumbling cliff. She later tells me she identified it as an Ocean Quahog, Arctica icelandica, which is still found on coasts around the UK. Apparently individuals can live for over 500 years. I pick up a few shells from the base of the cliff; they disintegrate in my hands. Kevin holds a rock with an embedded sea urchin fossil. I take a photo. Then I find a belemnite, a grey, bullet shaped fossil about two inches long. It was the beak or rostrum of an archaic squid-like animal that swam in an ancient sea over 100 million years ago. It doesn’t belong here: it is the wrong age. It must have been brought down from elsewhere at some point.

Walking back towards Covehithe we decide to continue further north up the coast. More crumbling cliffs, more bone trees, more sand martins. Every so often a skein of barnacle geese passes over. A peeping from over the water and we notice a small flock of sanderlings. Like descending notes they drop to the shore and skitter beside the waves. The sun smoulders faintly from behind a thick film of grey.

When Debbie and I met up it was as though hardly a day had passed. As I said, it’s been about 35 years since we saw each other at university. But we’ve been writing to each other — snail mail, and now email since lockdown. We were zoology students and are both in the Bird Club. Recently she sent me a shark tooth she had found at Ramsholt and gave me a book about Cenozoic fossils. I keep the small black shiny tooth on a shelf in the printer’s tray I use for natural finds. I examine it as I write.

Over the years my interest in wildlife has changed; I no longer need to regard nature with a scientist’s eye, no longer need to impose order on it in that sort of — I do that more with writing now. I am free of the shackles of measuring, dissecting and labelling, but I don’t want to lose my interest in identifying and learning about the natural world.

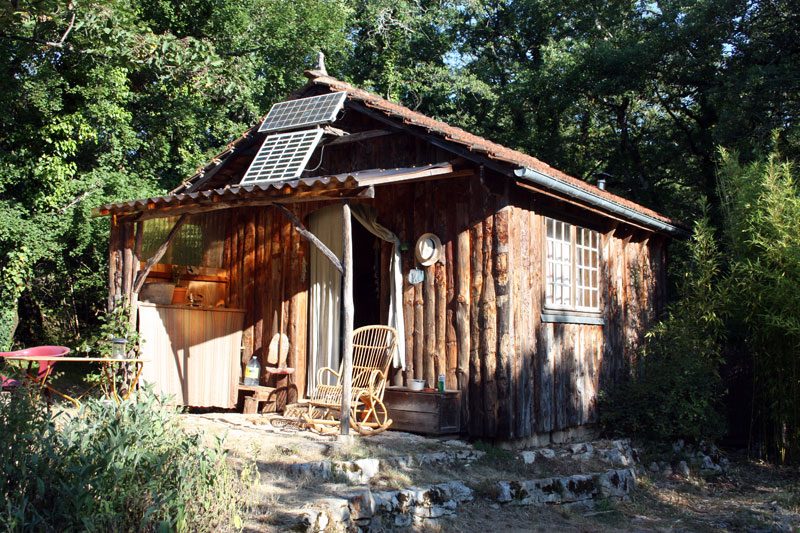

Covehithe beach is a palimpsest of stories both old and recent. I have vague memories of sleeping out as a student on a beach similar to this. Debbie was there with us. I miss the free-spirited, wild student trips we took racing around the country, camping in hospital car parks and freezing cottages, all for the adventure and to see rare birds. There’s nothing quite like sleeping out beneath the stars, beside a murmuring sea and driftwood fire, snuggled into a sleeping bag and talking about the meaning of life.

I must ask Debbie about that time on the beach. Does she remember it? Was it Norfolk or Suffolk or some vague stretch of coast somewhere around there?

The cliffs peter out and we arrive at Benacre Nature Reserve, a lagoon, sand bar, bird hide and private woodland. The bird hide is closed due to Covid-19. The sand bar is fenced off as it’s a breeding ground for little terns. The terns have finished nesting and there is just an assortment of gulls beside the lagoon and a cormorant on a post in the water.

The sun has vanished, grey-bellied clouds congeal in the west. Another skein of geese appears and forks southwards. I feel rain in the air.

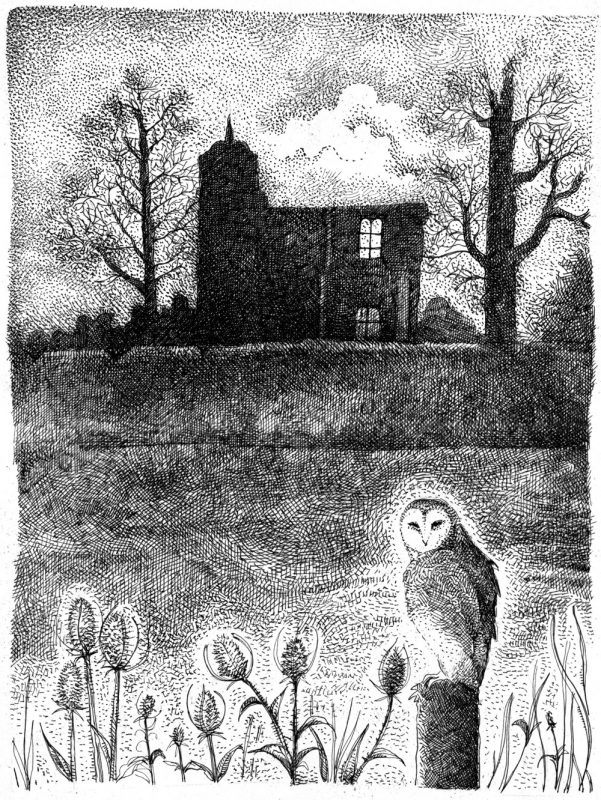

Returning to the hamlet of Covehithe, we decide to explore the church. St Andrew’s is a small, thatched church within the embrace of a much larger ruined church. The ruin is imposing. The towering flint walls have remnants of perpendicular arched windows. The church tower is still intact, solid and square like others I’ve seen in Suffolk that dominate the horizon from afar. The church ruins date from the 14th and 15th centuries. Later, in the 17th century, parishioners decided the church was too big to maintain, so they were granted permission to dismantle it and build a smaller church within its shell. I wonder about the congregation now — is it big enough to warrant the size of this small church, or will there be a yet smaller church? Churches within churches like Russian dolls. We cannot enter the newer church due to Covid-19, so we circumambulate the whole, taking photos and scrutinising the arches and columns from different angles.

A motley assortment of feral pigeons hunch on the lee side ledges in the ruins between tufts of wildflowers. Buddleias sprout from sheltered corners. I like the kingly stone heads with forked beards, the silent screaming faces of gargoyles. Walking into the ruin’s interior I notice a scattering of pigeon feathers, the sign of a scuffle or kill. Beside them is the soft, barred primary feather of a tawny owl. Are the feathers linked? Do owls go after pigeons?

The church was once much further inland. Looking at a 19th century map of the area, it is about a mile from the coast. A coastguard station marked between church and sea no longer exists and the road to it ends abruptly at the cliff edge.

I sometimes feel like those cliffs at Covehithe, weakened and weathered. Every so often, when life decides I haven’t suffered enough, it lands me a real blow and I end up in bed. So it is now I’m back home. I’m glad that this coastal stretch of Suffolk and Norfolk is allowed to be reclaimed by the sea. When I revisit it in years to come, perhaps the church ruin will perch on the cliff edge or lie in a romantic tumble of flinty rubble on the beach.