This piece appeared on the Landlines blog 24th August 2020.

Author’s Note

During an art and writing residency in a small cabin in King’s Wood, Kent, I wanted to see the nightjars that arrive in summer to breed. I was writing a book of wildlife encounters experienced during the hours of dusk, night and dawn. The nightjar’s haunting display has always been an event I try not to miss. One evening, my partner, Kevin, decided to join me.

***

A churring is audible from the birch trees at the edge of the wood. It is an uncanny sound, like the soft purr of an engine. My phone shows nine twenty, dusk. My partner and I follow in the direction of the sound.

It’s June on a still, mild evening in King’s Wood, Kent, and we are here looking for nightjars. The sky darkens from eggshell to powder blue. A small herd of fallow deer, grazing the forest track, slip away into the undergrowth when they see us. Keeping as quiet as we can we venture off the main track into an area of sweet chestnut coppice, the trees no more than two metres high. In a small clearing of birch saplings and grassy tussocks, we pause and wait, poised in anticipation, as white moths flitter between broom bush and rush stem like drunk angels.

It is not long before a dark shadow of a bird, scimitar-winged, like a giant swift, scythes the air above our heads. It is a glimpse, a moment of wonder. Then we hear the distinctive wing clap of the male as he performs to attract a female or ward off another male.

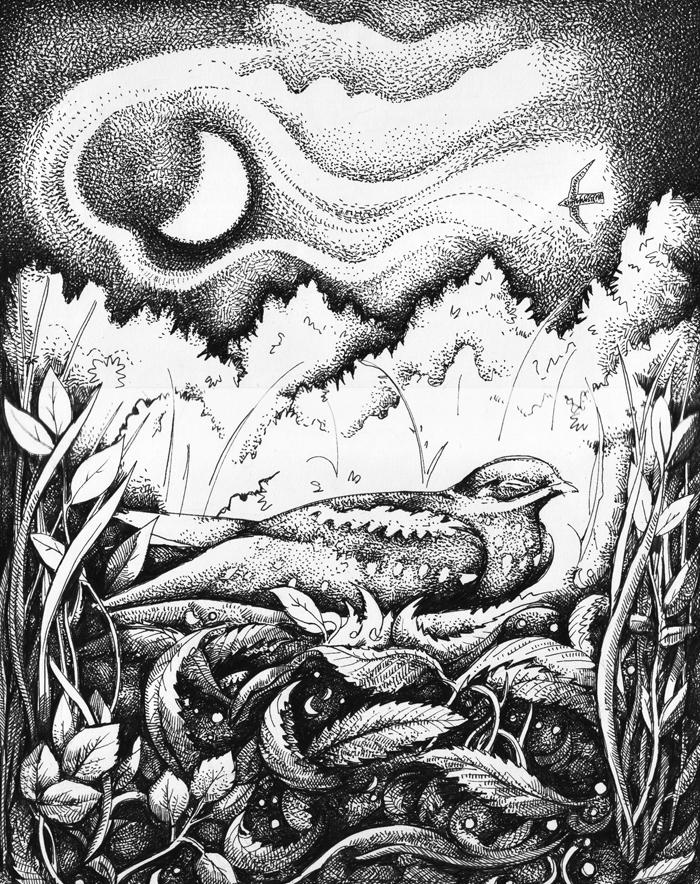

Nightjars emerge at dusk to feed on moths, mosquitoes and other flying insects, funnelling them into their wide mouths with the help of whiskers. As summer visitors, they arrive sometime in April from their wintering grounds south of the tropical rainforest in central Africa. For centuries they have attracted much superstition and folklore due to their strange call, unusual appearance and mysterious behaviour. They have been called by many names: dorhawk, nighthawk, puckeridge, puck bird, eve-jar, churr-owl, goatsucker. ‘Goatsucker’ stems from their ancient Greek name which meant ‘milker of goats’. It was believed that they sucked the milk from female goats; the birds often being found close to livestock, attracted to the insects around the animals.

The nightjar is a bird of the day’s edge, shear winged and shy, a bird of long summer evenings, of a world both familiar and surreal. Dream prophet, messenger, bristled-mouthed denizen sewing the remnants of day to the enfolding fabric of night.

In the chestnut coppice we wait and listen. The churring starts up again and the night purrs. We follow a narrow, overgrown path through the bushy trees into an opening with clear views of the now ink blue sky. We pause and look above the amorphous shapes of vegetation about us. Then, again a dark bird appears, flaps once or twice with long angular wings and circles over as though inspecting us before gliding out of sight. We have been gently lured into the nightjar’s realm.

Incongruous companions, the cracked pill of the moon and Jupiter stud the twilight sky.

The breeze picks up, swirling the froth of birch leaves; there is moisture in the air. Then the churring resumes, louder this time. Behind us on a dead branch high in a birch sits a solitary nightjar, black, steady and brooding. He’s a sentry of the night; a whiskered, feathered watchman; a night king who wants to be seen. A goatsucker. I watch him through binoculars while he churrs continuously for three minutes before flying off into the night.

On the way home I decide to return in daylight to check out the site.

The following day I’m out alone in nightjar territory. I wander the coppiced area dodging scrambling spiders with their white egg sacs in the grassy tussocks. Webs glisten and brambles snag at my trousers. Among birch saplings, I find burnt wood, heather, rushes. Below an overhanging sweet chestnut a dark patterned coil of canvas fabric shape-shifts into an adder, head up, languid, tongue tasting the air. I back away with care and watch where I tread.

Eyes to the ground now I wander further and am drawn to patches of bare ground in serrated shadow beneath some sweet chestnut bushes. With delight I find a broken eggshell in the earth and leaf litter. The eggshell is cream white flecked with grey and brown. Beneath more dry leaves I find another piece of shell. Two eggs! The young nightjars must have hatched in recent weeks and have probably fledged by now. I take photos and wrap the shells in a collecting box to take away and study later. I know that nightjars typically lay two eggs in a clutch and may have a couple of clutches a year. They are clearly still displaying here, holding territories and probably feeding young; I must make sure I don’t disturb them.

I wander back along the forest track, passing another coppiced area. I am brought to a halt when I see a brown mottled bird descend to the bare ground in front of me. It settles for a moment but then it sees me, hesitates and with a swift ascent flies up, a male with white wing and tail feathers visible. Silently he vanishes into the darkness of surrounding pines. From the trees I then hear a soft, continuous peeping sound. Could this be the young nightjars calling?

What a lovely piece about Nightjars. They are such enigmatic, mysterious birds from another realm of faeries and silver woods that come alive at night …

Thank you Clive 🙂